Want to hear a potentially novel idea? I think that D&D has therapeutic benefits. D&D as therapy actually makes sense to me. It can help deal with both depression and general anxiety. I say this because I have firsthand experience.

It took years for me to finally admit I needed help, but I did so last fall. After seeing a therapist for months, she eventually recommended I also see a psychiatrist. Between the two, I’ve learned I suffer from dysthymia (chronic mild depression), social anxiety, and potentially cyclothymia (a mild form of bipolar disorder). I’m undergoing treatment to help confirm or deny the cyclothymia diagnosis over the coming months.

I have some small authority about D&D helping me as well as helping some friends in similar situations. This isn’t just anecdotal stories like mine and those on Reddit that give credence to D&D as therapy. There’s an article on Geek & Sundry from a couple years ago about a Doctor of Psychology using D&D in therapy sessions to help teenagers. There’s even a popular twitter personality, The Id DM, who is a trained psychologist and often tweets and blogs about the intersection of D&D and psychology.

I would like to caution that D&D is not medicine, so it can’t treat depression. It’s not going to “solve” anxiety. I’m not a counselor. This blog post is well-intentioned but isn’t actual mental health advice. And finally, you should not consider D&D a replacement for proper counseling or treatment.

Backstory

I grew up in rural Kentucky. It’s not a bad place for lots of people, but it was a bad place for me. That part of Kentucky is about half midwestern, half southern. Many of the things you might envision of that kind of environment are true: stereotypical rednecks who like hunting, fishing, farming, nascar, bad American beer, and intolerance. Not everyone was that way, and not everyone who liked those things were bad people, but it was bad for me because that’s not who I am.

I grew up feeling out of place, never belonging. As a kid, I was poor and had no geeky outlets. None of my childhood friends knew what D&D was; I certainly didn’t. I didn’t play video games, read books or have much of any geeky entertainment until my middle school years. Regular access to a computer didn’t happen until my late teens. I was a young geek who was unhappy, trying to live life as a non-geek because I simply didn’t know there was any alternative.

This situation partially explains why, starting in my teenage years, I began to feel depressed. I didn’t know it at the time, of course. There was just enough toxic masculinity in my household that I knew I shouldn’t feel sadness or a sense of lacking for trivial things like ‘not belonging’. Toughen up, keep those emotions in check! RAWR BICEPS FLEX.

Teenage hormones probably made the problem worse. I didn’t have many friends in high school; even the kids who were bullied weren’t really geeky (or they hid it from everyone well), because being a geek just wasn’t a thing people did in the late late 90s in Kentucky.

Depression Lies

Just as with so many others, my depression was (and is) a sinister thing. It lies. It tell you that it’s not really depression. Thoughts like “you just can’t cope as well as others”, “other people don’t need help, why do you?”, “if you need help, you’re a failure” are always there. Needling. Nagging. Nettling. These persistent thoughts run renegade over the small part of you that maybe, just maybe, wants to seek help and feel better and be healthier.

If you feel like this, you are not alone.

And if playing D&D makes mute those thoughts — even if only temporarily — then you most certainly are not alone in that, either.

Depression Sucks

As I said, I’ve had depression since my teenage years. My mood swings go upward into frustration, anger, and resentment as much as they go lower in the more typical sadness, sullenness, and despondence. I’ll have days where everything seemed to just suck. One thing would go wrong; it could be a tiny random thing or a something with real but moderate impact. I’d have some reaction to the event that was out of proportion. A friend would cancel last minute instead of hanging out with me. I’d realize I forgot to buy more milk at the store after getting home. Priorities at work would shift unexpectedly. The point is, the trigger wasn’t the real reason I’d start feeling miserable for hours or days, they were literally just a trigger.

During these times, I felt hopelessly unhappy, obsessing with my thoughts. I’d relive conversations, play scenarios over in my head. Usually I’d be analyzing actions looking for what I’d done wrong. Let that sink in. I’m such a harsh critic of myself that I blame myself for being depressed. And this would persist until I was able to forget about it. Enter D&D.

D&D Has Helped With My Depression.

I was in my younger 20s when I first found friends who played D&D. In a number of ways, these friends and D&D changed my life. I finally had found people I connected with. There was a small group of people to which I finally found belonging.

I had a core group of 3 friends, and we spent the better part of a decade being inseparable and playing D&D together. The four of us would play games, adding in a secondary roster from a group of another 7 or so friends who’s availability shifted. Three player D&D parties, 8 player parties, games with co-DMs, outlandishly powerful games (hello 3.5 Gestalt alternate rules), games with lots of story, and games that mimicked Diablo’s mindless hack’n’slash.

We played it all, we grew close together as friends, and we learned a hell of a lot about each other. And this whole time I suffered with depression, but I just wasn’t willing to admit it or label it that way. I never referred to it as such even when I admitted I was unhappy. But looking back, something truly astounding becomes clear — my depression was muted while playing D&D. I had found my escape.

D&D was my therapy I didn’t know I needed.

I didn’t go to therapy. I didn’t seek help. I wouldn’t — couldn’t — even admit I needed it. But without knowing it, I used D&D as therapy all the same.

D&D As Therapy Helped With My Depression.

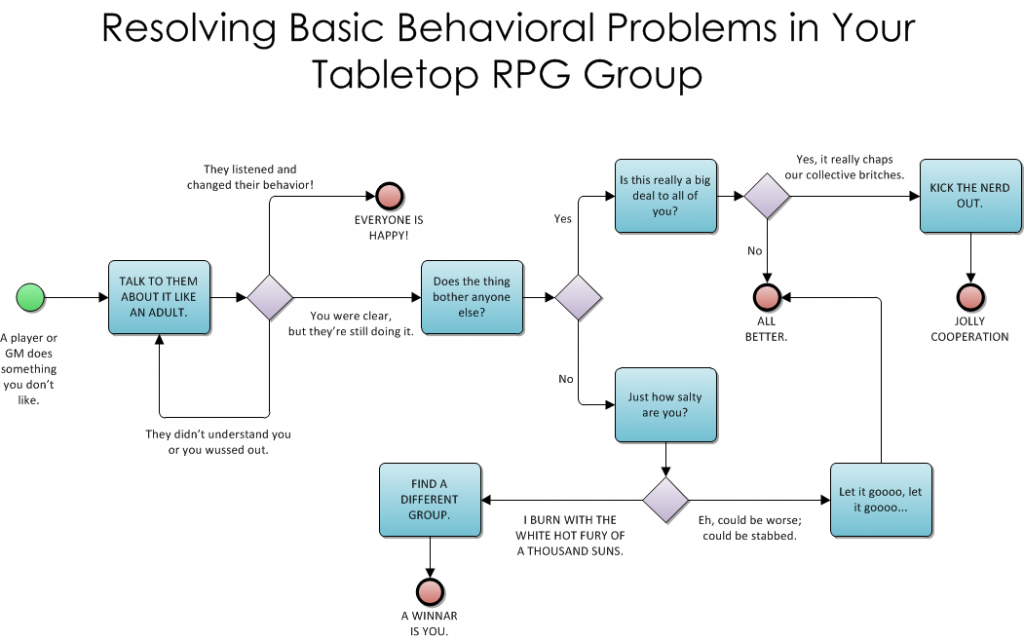

Just like how D&D advice depends on your play style, using D&D as therapy will depend on your personality and mood. But I bet for a lot of people, D&D may be able to help if you’re suffering from depression or anxiety.

I truly, honestly believe D&D as therapy is an amazing outlet. It’s literally the perfect escape from all of life’s shitty little problems. You get to pretend to be someone else, living somewhere else, and doing something else. In D&D there’s no jobs or commutes or stressors like there are in real life. For the things in game that might bother you, you get to set them on fire or hit them with an axe, so that’s cathartic as well.

D&D Also Helped With My Social Anxiety And Social Skills.

In my case, I primarily played with friends. In this situation, I was hanging out entirely with people I wanted to see, playing a game I wanted to play, and having some of the best fun of my life. But due to so many of our friends having wildly unpredictable schedules, we’d need to reach out for another player. Since I have mild social anxiety, talking to new people isn’t normally my thing.

But I loved talking to new people in a controlled manner and about things I was passionate about. Such as, you might correctly deduce, adding one player to a controlled group of friends about D&D, which I just so happen to be passionate about. D&D let me talk to people, and when I started DMing I really got to work on intra-personal skills.

I forget that I’m depressed while playing D&D, even for those really bad days. Future sessions become a time to anticipate, with my excitement sometimes literally feeling like it’s unable to be contained. Hell, I clearly even enjoy writing blogs about D&D. And lately I’ve been digging into the online D&D community, checking out indie creators, and feeling how much joy it can bring people.

Maybe D&D Can Help You Too

If you need it, I hope that D&D as therapy can bring you the same relief.

As always, if you want to talk about the article hit me up on twitter. And a special consideration for this article: if you are feeling depressed and want someone to talk to, my twitter DMs are open. I at least know what it’s like, I won’t judge, and I firmly believe no one should have to suffer depression alone.

If you’re mentally hurting, please seek help. Find a therapist or confidant. Go to a priest if that’s your thing. If you’re seriously hurting and need emergency mental care, consider going to the Emergency Room or calling the Suicide Hotline (in the US) at 1-800-273-8255.